A brief history of Coombe Keynes

Pre-History to Victorian Times

The parish of Coombe Keynes covers some 25 square miles (well over 2,000 acres) at the western rim of the Purbeck Hills. The village takes its name from the coombe (or valley) in which it stands and the Keynes family who were lords of the manor from the 12th to 14th centuries.

The population of the parish has fluctuated considerably. From 32 adults in the 11th century it rose to maybe several hundred before the Black Death in the 14th century when it probably fell to half that number and took over 300 years to recover fully. According to the Hearth Tax returns, the population was 170 in 1662. In the 1801 census 93 people lived in the parish, rising to 135 in 1841 and 163 in 1861. But by 1971 the population had fallen to 78 and has stayed around that number since.

Early History

A number of pre-historic features exist in the area, particularly six barrows on Coombe Heath to the east of the parish. Traces of ‘celtic’ field boundaries dating from the Bronze Age have been found near the coast but not around Coombe Keynes. Archaeologists believe that parts of the old field system continued into the Roman period based on pottery that was found at the Newlands farm site near West Lulworth.

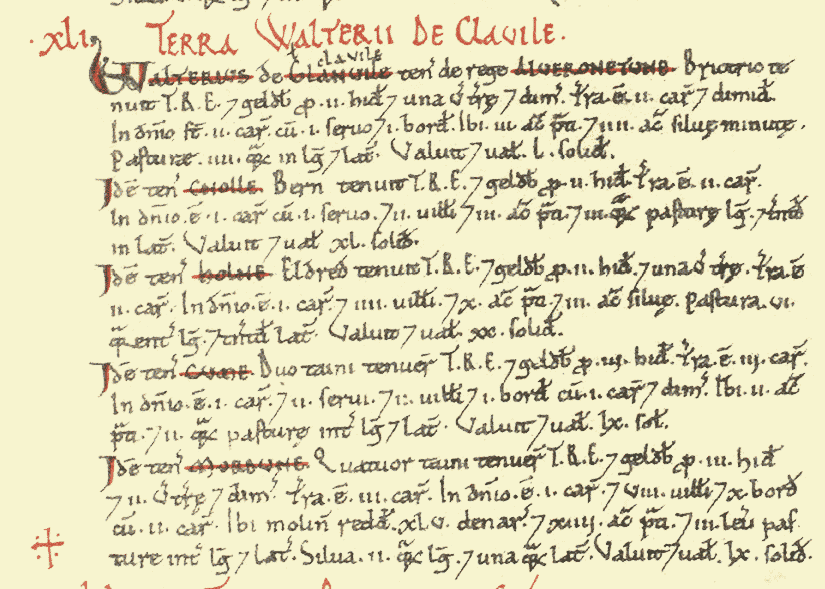

After the Norman Conquest, the feudal system meant that lands were held directly from the king whose Norman vassals and various other French and Breton adventurers expected rewards in the form of lands. Encouraged by the dead King Harold’s mother Gytha to join a wide-spread resistance to the Normans in the south-west, the four Dorset boroughs seem to have suffered severely as William’s forces advanced to suppress the revolt. The manor of Coombe Keynes is recorded in the Doomsday Survey of 1086.

Coombe Keynes manor was held principally by Gilbert Maminot, bishop of Lisieux, a close ally of King William, and Hugh Maminot held it from him. A smaller part was held by Walter de Clarville, another Norman knight. Well over half the manor was arable land situated on the easily cultivable clay/flint soils that lie on the top of the chalk downs. The manor was worth £10 in total. On it lived 16 bordars, serfs and cottars together with 8 villeins. There were 10 ploughlands worked by 9½ plough teams each covering 120 to 130 acres.

Walter de Clarville’s holding was described in the Domesday Survey as:

The same (Walter) holds Caime. Two thegns held it in the time of King Edward and it paid geld for 3 hides. There is land for 3 ploughs. In demesne there is 1 plough and 2 serfs and 2 villeins and 1 bordar with 1½ plough. There (are) 2 acres of meadow and 2 furlongs of pasture in length and width. It was and is worth 60 shillings.

The Middle Ages

In the early twelfth century Ralph de Keynes married the daughter of Hugh Maminot. Her dowry included the manors of Tarrant and Coombe in Dorset and Somerford in Gloucestershire. The modern names of all three are based on him – Tarrant Keyneston, Coombe Keynes and Somerford Keynes. His family, who were already tenants-in-chief of nearby Chaldon Herring, now bought the fees of the remainder of Coombe Keynes from the de Newburghs and the bishop of Salisbury.

By 1276 they had sold half the manor (called Southcombe) to John Paynell and 60 years later William de Keynes had to grant tenure of the whole manor to Geoffrey de Donechurch. Thus by the middle of the thirteenth century the feudal system of land tenure had changed to the orderly operation of land exchanges for financial gain.

Coombe Keynes was a good example of a medieval nuclear village which stayed that way until the end of the eighteenth century with open fields round the village. The villagers held their strips, usually an acre or half-acre each in area, in the North field, situated either side of the present road to New Buildings, and the South field to the south of the church.

Extensive settlement remains have been found by excavation in the pasture land immediately east, north-east and south of the church. Further remains were found 300m north-east of the church and on the north side of the present road through the village. These remains show that the village was considerably larger and contained more buildings than it does today.

The Black Death entered England through Melcombe Regis (part of Weymouth) in June 1348. In the parts of the country affected by the plague half the population perished. There are stories of a mass grave in one corner of the churchyard where no-one has been buried since. The deaths included the vicar. A new vicar was instituted in October of that year at the height of the plague. Throughout the country, wages rose and rents fell as a consequence of the reduction in population numbers.

The male line of the Keynes family died out in 1375 with the death of John de Keynes. The last of the line to hold the manor was Elizabeth de Keynes who died a few years later. We do not know how close an interest the Keynes family took in the village; they did not reside here but in Tarrant Keyneston.

In the early fourteen hundreds waste land was tilled to provide extra cereal growing soil but as the fifteenth century progressed sheep farming was extended to replace it. In Coombe Keynes around 425 sheep were shorn annually in the mid-1460s. This trend showed the growing consolidation of the interests of large landholders at the expense of the remaining peasant proprietors on their estates.

Religious and Political Turmoil

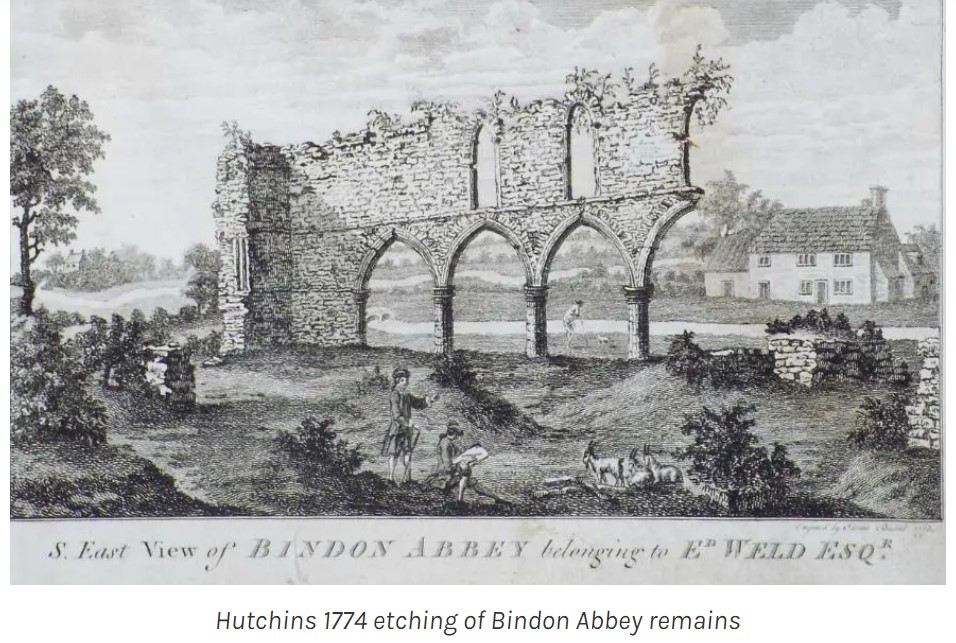

Under Henry VIII’s Dissolution of the Monasteries, the Cistercian Abbey of Bindon, some two miles to the north of Coombe Keynes, was demolished in 1539. Little remains of it now as a great many of the stones were used for building cottages in nearby villages. Its twelve bells were said to be distributed to churches at Wool, Coombe Keynes and Fordington, near Dorchester.

During the reign of Henry’s son Edward VI, the Reformation became more radical: images and paintings in churches were condemned, the clergy were allowed to marry and all clergy were forced to use Cranmer’s English-language prayer book. Not all people were prepared to accept these new ideas. However, from the point when Queen Elizabeth was excommunicated by the Pope in 1570, Dorset was on the front line in resisting the Spanish invasion and every English Catholic was regarded as a potential traitor.

Many important events of the Civil War took place in Dorset as the warring armies roamed the land. No major battle was fought in the county but it was of great strategic importance since its ports could facilitate or repel foreign aid. After the restoration of the Catholic monarchy with King Charles II in 1660, Lyme Regis saw the Duke of Monmouth’s protestant rebellion. This was concluded in 1685 with the despatch of Lord Chief Justice Jeffreys to the South West to deal with the hundreds awaiting trial. At Dorchester, 74 were executed and 175 transported to the West Indies after the “Bloody Assizes”. The memory of the executions remained in the towns and villages of Dorset for many years.

The Weld Estate

Ownership of the manor passed from the Keynes, through the Newburgh family, eventually to James, Earl of Suffolk who in 1641 sold it to Humphrey Weld. Apart from a period of sequestration, it has been held by the Weld family ever since.

By the middle of the 17th century there was a relatively thriving yeoman community with birth and death rates balancing out with the amount of land that could support each family. For every two or three acres of arable each smallholder had the right to enjoy one acre of pasture for his animals.

After 1688, when the ‘Glorious Revolution’ had removed all traces of arbitrary feudal restraint, the unrestricted growth of capital and new agricultural techniques threw into sharper focus the divergence of interests between the rising tenant farmers/gentry and the now declining smallholding/yeoman class. The ancient system of open-fields and extensive commoners’ rights of pasture were simply incompatible with more intensive methods of agriculture.

There was still much anti-Catholic prejudice but the Catholic Weld family was prominent in Dorset affairs. During the 1745 Jacobite rebellion, Edward Weld was arrested on suspicion of being involved but later released. The widow of his son, Mrs Maria Fitzherbert, secretly married George, Prince of Wales but was later discarded.

In 1786-7 Thomas Weld was allowed to build the first Roman Catholic church in England since the Reformation – provided that it did not look like a church. “Build a family mausoleum and you can furnish it inside as a Catholic chapel if you wish” the king is supposed to have said. And the Pope created his son, Thomas, a Cardinal.

Between 1760 and 1780 the intensification of enclosures, the reduction in yeoman farmers and a steady population increase did not affect too severely the life-style of the average day-labourer or smallholder. But between 1780 and 1795 more rapid population increases and unprecedented inflation resulting from the continental wars with Napoleon caused a virtual breakdown of social self-sufficiency on the Weld Estate.

John Sparrow’s 1770 map of the Weld Estate –

reproduced by kind permission of the Dorset History Centre (D-WLC/P/1/5 )

Conflict in the Countryside

In 1793 half the households in Wool and Coombe Keynes had between 4 and 7 members compared with less than 2 percent a century earlier. Subsistence turned to destitution as household incomes could not keep up with the number of dependants and the rising prices of food, or pay the rent. Farmers were obliged to pay even higher poor rates to supplement the inadequate wages of their men by means of poor-relief.

Wheat and bread prices jumped with the war against France. With such widespread poverty, a decision was taken in 1796 by local landowners including Thomas Weld and James Frampton of Moreton to build a substantial workhouse in Wool. Only the most desperate were admitted and if able-bodied they were expected to contribute most of their wages towards the cost of running the institution.

The ending of hostilities in Europe after 1815 brought no relief to the sufferings of the countryside. A serious bread riot broke out in Bridport the following year. Farmers cut costs to the bone by reducing wages and mechanising their operations, for example by introducing threshing-machines. These measures caused a shrinking labour market for the rapidly expanding rural population to which was added ex-soldiers from the wars. The result was near catastrophe for the rural population.

Alarmed by the Peterloo mass demonstration in 1819, the Tory government decided to stand firm. Freedom of meeting, of speech and of the Press were severely restricted by the Six Acts of 1819 of which one of the strongest supporters was Lord Eldon of Encombe near Corfe Castle. Dorset farmers, protected by the Corn Laws, were keeping their labourers’ wages low. After a disastrous harvest in 1829, the first rising took place in 1831. Squire Frampton of Moreton read the Riot Act to disperse the mob. The ringleaders, as with the “Tolpuddle Martyrs”, were transported.

The old forms of farming had changed for good. In the 1840s most land in East Lulworth and Coombe Keynes was held by proprietors with 100 acres or more and the old open-fields had disappeared. Joseph Weld put the estate to more intensive use in the generally prosperous state of British agriculture between 1835 and 1875. He built more and better farm buildings, he removed rough pasture and he installed efficient drainage. This was the golden era of economic viability for the Weld Estate.

Agriculture remained the major industry of the village with two farms, East and West, situated near the centre of the village. There was also a brickyard which worked the Reading beds on the western edge of the village and which from the middle of the 19th century into the 20th produced a steady supply of bricks and tiles. Many of the Victorian buildings in the locality, such as the Black Bear in Wool, are built from the easily identifiable red Coombe brick.

However, the ever-present threat of poverty combined with the decline of casual employment led to a radical break up of the traditional social structure of agricultural households. Such pressures contributed as much as over-population and enclosure to the final demise of community life in rural Dorset. Heads of households could no longer maintain children and relatives permanently living at home. Young females left in droves for the rapidly expanding residential resort of Bournemouth which grew from a small watering place in 1871 to a fair-sized town early in the 20th century.

20th Century

This section is still work in progress.

Can you help? Did you or your relative have a connection to the village in the last century? If so, we would love to hear from you. We’re starting to collect accounts of villagers and visitors lives as part of the Coombe Keynes History Project. To learn more visit the CKHP page.

We already have an invaluable anecdotal account of the years 1933 to 1967 by Michael Drew of his family as well as the charming memories of Gwendoline Wilkinson, age 9, evacuated to Coombe Keynes in 1940.

Acknowledgements

Historic Landscape of Weld, edited by Lawrence Keen and Ann Carreck

Hutchinson’s Dorset

A History of Dorset, Cecil N Cullingford, 1980, ISBN 0 85033 255 9

A Backward Glimpse of Wool, Alan Brown,1990, ISBN 0 9517006 0 X

The Changing Face of Wool, Alan Brown, 1999,

More Memories of Wool, Alan Brown, 2008.